It was the strangest book that he had ever read. It seemed to him that in exquisite raiment, and to the delicate sound of flutes, the sins of the world were passing in dumb show before him. Things that he had dimly dreamed of were suddenly made real to him. Things of which he had never dreamed were gradually revealed.

It was a novel without a plot and with only one character, being, indeed, simply a psychological study of a certain young Parisian who spent his life trying to realise in the nineteenth century all the passions and modes of thought that belonged to every century except his own, and to sum up, as it were, in himself the various moods through which the world-spirit had ever passed, loving for their mere artificiality those renunciations that men have unwisely called virtue, as much as those natural rebellions that wise men still call sin.

The Picture of Dorian Gray (chapter 10) – Oscar Wilde

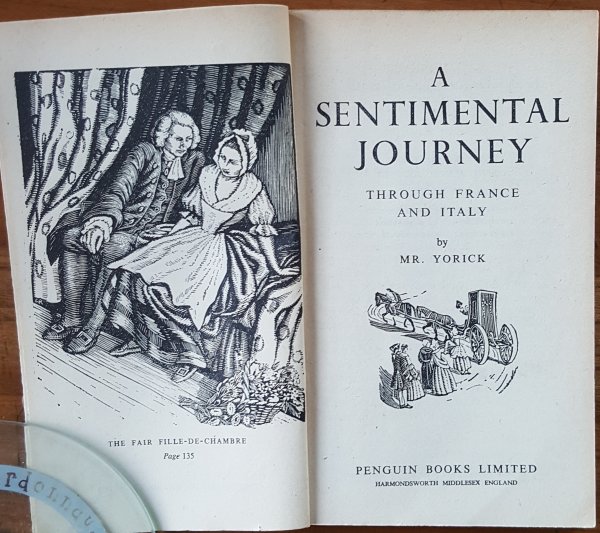

When I recently read ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray‘ I assumed that the book referred to as the inspiration of Gray’s sensual explorations and obsessions was simply a device invented by Wilde, so I was surprised to discover that in fact the book actually existed. Wilde confirmed that À rebours by Huysmans was the book during his failed libel trial against the Marquess of Queensbury in 1895, and I found that not only did it exist but that a copy was already on my shelves, and had been for probably twenty years although sadly neglected, in form of the Penguin Books translation of 1959 with its title translated as ‘Against Nature’, it is also known as ‘Against the Grain’.

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans, who wrote as Joris-Karl in a tribute to his father, was a career civil servant, author and art critic living in Paris between 1848 and 1907 and was far from the character of the aesthete, Des Esseintes, who is the ‘hero’ of Against Nature. I put the word hero in quotes advisedly as the Duc Jean Des Esseintes is far from heroic being “a frail young man of thirty, who was anaemic, with hollow cheeks, cold eyes of steely blue, a nose that turned up, but straight, and thin papery hands”. This then is the subject of the book with other characters reduced to mere cyphers as he keeps himself away from all other human contact as far as possible. Even arranging that his two servants rarely see him and they live in a sound deadening apartment in a separate part of the house so that their existence doesn’t impinge on the solitude and quiet so desired by their master. Huysmans is clearly highly educated and very well read as demonstrated by the third chapter of the book, in this edition at least as translations vary between the chapter breaks, which is largely a harangue on the Latin writers from Virgil, just before the Christian era, to the eighth century Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical authors whilst featuring the Des Esseintes library.

It is only fair to add that, if his admiration for Virgil was anything but excessive, and his enthusiasm for Ovid’s limpid effusions exceptionally discrete, the disgust he felt for the elephantine Horace’s vulgar twaddle, for the stupid patter he keeps up as he simpers at his audience like a painted old clown was absolutely limitless.

Translation by Robert Baldick – Penguin 1959

…

Sallust, who is at least no more insipid than the rest, Livy who is pompous and sentimental Seneca who is turgid and colourless, Suetonius who is larval and lymphatic, Tacitus who with his studied concision, is the most virile, the most virile, the most sinewy of them all. In poetry, Juvenal, despite a few vigorous lines, and Persius, for all his mysterious innuendos both left him cold. Leaving aside Tibullus and Propertius, Quintilian and the two Plinies, Statius, Martial of Bilbilous, Terence even and Plautus whose jargon with its plentiful neologisms, compounds and diminutives attracted him, but whose low wit and salty humour repelled hm.

Well that just about sums up most of the famous ancient Roman writers and presumably these are not just the supposed opinions of Des Esseintes but that of the author as well, the denigration of the Latin poets and later biblical scholars continues for several more pages as he moves through history. Two more chapters near the end of the book perform similar attacks on French literature but as these concentrate on liturgical authors and what Huysmans himself describes as minor writers I found these far more difficult to read as I wasn’t familiar with the works discussed. Another chapter represents the Des Esseintes art collection where Huysmans has him own Gustave Moreau’s ‘Salome Dancing Before Herod’ and ‘The Apparition’ both of which are described at length along with prints by Dutch artist Jan Luyken of medieval torture scenes along with other works. We are now roughly a third of the way through the book and I can see the fascination that this book must have had for Oscar Wilde, the descriptions are sumptuous, if at times macabre, but the book is so unlike anything else I have read apart from the work that it clearly inspired, that of Dorian Gray. Here we have a character determined to absorb all they can from the great art and literature to the exclusion of anything and anyone else, a man with a fine eye to colour and the effects that different lighting has upon it and a determination to appreciate all that he sees as good. A man who lives almost entirely in artificial light as he wakes in the evening and breakfasts then does as he pleases before dining in the early hours and going to bed as the sun rises so what looks good by candlelight is an essential consideration.

Later chapters cover, amongst many other things, his fascinating, although short lived collection of hot house flowers, deliberately chosen to look fake in texture and colours in contrast to his existing man-made floral displays that are masterpieces of realism. A detailed account of his bedroom also features where again artifice triumphs over nature with fine materials displayed to mimic the austerity of a monks cell such as the yellow silk on the walls to represent the paint on plaster of his original subject. All in all I loved this book and I’m glad I read it after ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, its very obscurity up until then had caused me to bypass in my shelves until I was truly ready to read it. I must admit I expected a difficult read and was pleasantly surprised as to how quickly I was absorbed in the work and apart from the previously noted French literature issues the 200+ pages largely flew past. Admittedly with several pauses where I looked up various things such as some of the paintings or flowers itemised by Huysmans which I was not familiar with, but that he had piqued my interest with to make sure I fully appreciated the points he was making and the exactitude of his representations of them,