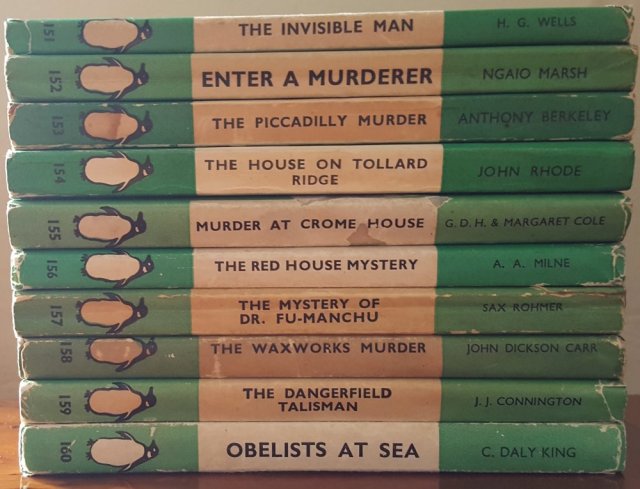

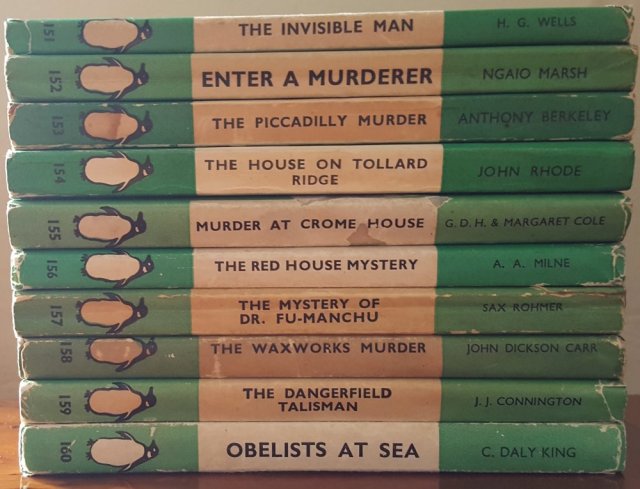

The continuing exercise of reading all ten of the crime novels published by Penguin Books to mark reaching 150 titles. All the volumes I’m reading are the first edition, first impression copies published eighty years ago this month (August 1938). It’s been fun reading these old paperbacks so far and now I have just four to go, for part 1 see here, and part 2 is here. I’m writing this blog as I’m going along so the book is fresh in my mind as I write about it so lets see if I can get through the final four volumes in the coming week.

157 – The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu – Sax Rohmer

Before opening this book I should say that this is the one I am least looking forward to. Although I’ve never read any of them the Fu-Manchu stories have never appealed possibly due to childhood memories of bad black and white films which I never watched to the end, or even half way through. Here’s hoping the book is better…

It wasn’t. It was everything I expected and worse, full of casual racism, extraordinary plot devices and ridiculous language I completed it only so that I could write this entry. Hopelessly jingoistic with the white race threatened by the yellow peril as it was regularly put, each chapter seemed to include another fantastical creation of poisons unknown to man, or traps created by mutant puffball mushrooms that react to light or other idiotic suggestions. The book fails on almost every level those rules suggested by A A Milne that I mentioned in the last blog with each time the ‘heroes’ get into trouble or a new murder is attempted yet another ‘fact’ is revealed just to get a solution with no pre-amble to involve the reader in the plot. Even more annoying is the constant xenophobia displayed by Rohmer where anyone who isn’t white is treated as a villain.

The language used also fails Milne’s tests with the servant of the first victim pointing out a way in with “Up yonder are the study windows sir” and the same sort of anachronistic rubbish is put in the mouths of several other characters. Nobody since Shakespeare has ever phrased a statement like that and he would have been writing a poetic play not accurately reporting actual language used.

Frankly avoid Sax Rohmer and I’m astonished to find that he is still in print.

158 – The Waxworks Murder – John Dickson Carr

What a dramatic improvement, Inspector Bencolin of the Paris Sûreté is a wonderful creation of a master of detective fiction. The plot is complex linking two murders of young women, a disreputable club in the area of Pigalle, itself a disreputable district of Paris, and Parisian high society. That an American, living in England, should write five novels about a detective in France is surprising, that they should be so atmospheric (at least on the evidence of this volume) is remarkable. The Waxworks Murder (US title – The Corpse in the Waxworks) is the fourth Bencolin book, I also have the first (It Walks by Night) in the Penguin edition; however although Penguin published many other detective stories by Carr these mainly feature his best known detective Dr Gideon Fell.

Carr plays fair with the reader, there are lots of clues and as many red herrings, paths to enlightenment and just as many dead ends which makes the book my favourite of the ones so far, you really get a mental workout following the various strands of the plot. That the tension is literally maintained until the final sentence is also a tribute to the skill of the author and I can definitely say that I hadn’t worked out the solution until it was revealed and then as the bits I had missed were explained it all became clear. I loved that we were led by Carr to suspect yet another person in the last chapter before the denoument only to have that apparently logical step demolished by the detective a few pages later.

The tension builds as the book progresses and by the time I reached the last seventy five pages there was no way I was going to put it down until it was finished even though I really needed to be doing something else. I will have to try the Dr Fell stories after I have read It Walks by Night and then the Henry Merrivale tales that he wrote under the name of Carter Dickson. He may be a great mystery writer but he was rubbish at Pseudonyms

159 – The Dangerfield Talisman – J J Connington

J J Connington was actually the Scottish chemist Alfred Stewart who wrote over two dozen novels as Connington and several factual works under his own name. The Dangerfield Talisman is his fourth novel and unlike all the other books I am reading as part of this series it is a case of theft rather than murder that concerns the participants. Apart from that it is a classic British country house case that has been very well written with two separate but linked puzzles to be solved, what is the Dangerfield Secret and where is the Dangerfield Talisman?

What is also a lot of fun is that there isn’t a ‘detective’ figure as such, several of the house guests have a go at solving the problems and manage to rile the others by making unjustified accusations. This is not a gathering you would want to be part of. Having said that I was worried about the start of the book, there seemed to be a lot of interest in bridge (which is a card game I don’t play or even vaguely understand) and then a chess board diagram was added (which looked fairly straightforward but clearly wasn’t if it was to be the basis of part of the story). I had a horrible feeling that these games were going to be highly significant to the plot in which case I would be left without significant clues. In fact you don’t need to know anything about either game, the bridge games stop after a couple of chapters and the chess board only really comes into it’s own towards the end of the novel. As for who took the Dangerfield Talisman I hadn’t a clue until it was revealed, not that there weren’t hints, just that I had not understood their significance. The Dangerfield Secret and more importantly the solution to it I had worked out though before it was explained.

Connington is definitely worth reading more of, five of his novels were published by Penguin and I have two others. One of the ones I’m missing is his science fiction book Nordenholt’s Million first published in 1923 and which is probably the earliest ecological disaster novel with a bacteria destroying farm crops around the world. Definitely one I’m going to seek out.

160 – Obelists at Sea – C Daly King

Last one… and the first question is what is an ‘obelist’? It turns out that King invented the word and defined it at the start of the book as “An obelist is a person who has little or no value”. Unfortunately when he re-used the word in two more novels “Obelists en Route” and “Obelists Fly High” he redefined it as “one who harbours suspicion”. At least if you are going to invent a word then be consistent. Penguin only printed this one book by C Daly King and at 312 pages of quite small print it’s easily the longest of the ten I have set myself to read, it is now Monday morning and I need to finish the book and complete this review for tomorrows post.

Well the plot was good and the conceal of the murderer was also well done but the writing style made getting through this book hard work. C Daly King was a psychologist and he made his detectives (for there is a group of them on their way to a conference on board the ship) also psychologists, although from differing branches and opinions. This could have worked well but King couldn’t resist putting in pages and pages of psychological exposition which was incredibly dull and just slowed the plot down dramatically. It was all completely unnecessary but you felt you had to read it in case there was a point to any of it. In fact there was virtually no point to the vast majority of this and even other characters in the book were bored of it eventually. But even then, after admitting that it was dull and largely confusing as they simply contradicted each other King couldn’t help himself from making some more pointed remarks about a branch of his own profession. The book is split into six chapters, an introduction to the crime, one chapter for each of the four psychologists to try to solve it according to their own theories and practice and then a final chapter that finally explains what actually happened and why all four were wrong, although each had grasped part of the solution.

It’s a pity that this was the last of the set to read as it has let me down from the high quality of the previous two but it has been an interesting exercise although next time I set myself to read ten novels in one month I’ll start before the 12th.